-

-

-

Infrastructure space/

Dubravka Sekulic:

Eurovision

-

Months before my 9th birthday, Yugoslavia won First Prize at the Eurovision Song Contest. It was 1989, and I still remember the anchor Oliver Mlakar saying something like, “now we can all drink a glass of cold water, it is finished, we won,” just before the last country performed and was able to read out the votes. Eurovision was coming to the only communist country through the competition. And then, a year later, everything was different. The Berlin Wall was down, the German reunification was well under way, and Yugoslavia was counting its last days. At the 35th Eurovision contest in Zagreb, Toto Cutugno won with a song called ’Insieme: 92,’ which celebrated the scheduled signing of the Treaty of Maastricht and the formation of the European Union. I think of it as being one of the most ironic moments in the story of Europe.

-

Video still

-

- European Broadcasting Union Logo

- Since 2004 ESC generic logo was introduced to create more visual consistency

-

After World War II, European countries were no longer competing on battlegrounds, but on the field of technology. Television was symbolic of a country’s technological development, and each country was busy developing its own broadcasting protocols. The most important parameter was the size of image defined by the number of lines per second broadcasted over a continuous analogue signal. Protocols in use ranged from the 405-line standard used by the BBC in the UK, developed by the EMI Research Team, to the 819-line standard used in France, developed by René Barthélemy. Although a third one, the 625-line standard, became de facto standard and the only one used for colour transmission, France continued to use its 819-line standard until 1984 when the last transmitter was closed down. This coincided with the presidency of François Mitterrand, who implemented the 819-line broadcast standard in 1948. France stuck to the 819-line standard so long not only because it was more advanced, but also to protect the national market. Supranational broadcasting was a difficult and complex technical issue, firstly because of converting between varying numbers of lines per second and frame rates used by different countries, and secondly there was little incentive for these countries to synchronise protocols due to the limited number of programmes one could broadcast in a broader region.

-

“Eurovision song contest is not a political event.”

Svente Stockselius, executive supervisor of the 2005 ESC -

Signing of the Treaty of Rome

-

Initially, 26 members both from East and West Europe created a standardising body, the International Radio and Television Organisation in 1948. Already in 1950 however, political tensions resulted in some members, mostly from Western Europe, leaving the organisation to form the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). The EBU’s main purpose was the promotion and coordination of common standards. In the beginning this process was slow going and the only way out of the deadlock seemed to be the establishment of the Eurovision Song Contest in 1955. The idea came from Marcel Bezançon, the Swiss president of the EBU and was modelled after the Sanremo Music Festival. The Eurovision Song Contest began in Lugano, Switzerland in 1956 and was the first major event in which European countries would compete against each other for some kind of European title (even preceding the European Football Championship which only held its first competition in 1960). Moreover, it was the only event to be broadcast live in all seven participating countries.4 The rest is history: when the second contest was held in Frankfurt, in 1957, ten countries participated. Six of them, a few weeks later, signed the Treaty of Rome, the decisive document for the foundation of the European Union.

-

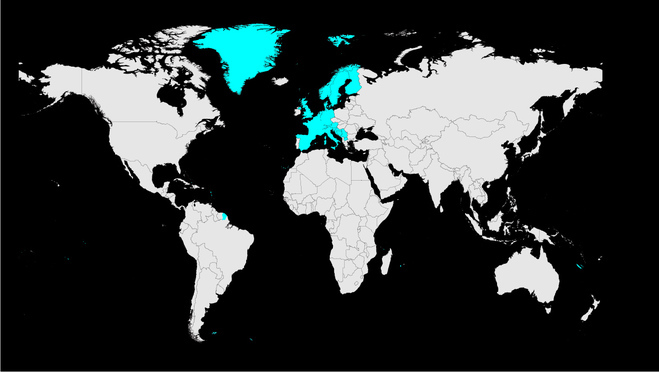

Countries that took part in the first European Song Contest in 1956

-

As I began travelling to the European Union after 2000, the easiest way to explain that Yugoslavia had never been “behind the Iron Curtain” was not by mentioning Tito and his break with Stalin, but Yugoslavia’s participation in the Eurovision Song Contest from 1961 and onwards. We shared common childhood memories. Subscription to Eurovision somehow meant being part of Europe.

-

Countries that participated in the 6th ESC in Cannes, France in 1961

-

The International Radio and Television Organisation ceased to exist on January 1st, 1993 when it merged with the EBU. Consequently, the next contest was flooded with former Eastern Block countries, finally eligible to take part in Eurovision.1 Something like that had happened a year before when three new states formed after the break up of Yugoslavia – Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Slovenia – joined the contest. Bosnia and Herzegovina, only barely officially recognised as a country, even sent contestants that were selected in Sarajevo under siege. The name of the song “The Pain of the Whole World” sung by Fazla conveyed what Sarajevo was going through to the rest of Europe. The message, however, could not be heard in Yugoslavia, as it was banned from participating in or even broadcasting the contest due to UN Sanctions imposed in 1992. These sanctions not only applied to the economy but also to culture and sport. Furthermore, for former Eastern Block countries participation in Eurovision also marked a change in the status of television. It became a commodity instead of a privilege. Some of the new Eurovision countries even changed their colour system, switching from SECAM to the more widespread PAL standard, which was used by all Western European countries except France.

-

The choice of SECAM over PAL in the Soviet sphere of influence was not just a technical affair. The German Democratic Republic insisted on adopting a standard that would be different from that of its Western neighbours. This was meant to prevent the smuggling of television sets, and the watching of programmes made in West Germany. A country’s willingness to change its national agenda and adopt different standards in order to participate in Eurovision, shows that standardisation is much more than a neutral, technical issue, and that Eurovision itself is a bit more than just a singing contest. The popularity of the contest transformed it into a pervasive soft power, based on three simple rules.

-

Rule #1: Have a national broadcasting corporation which is a member of the EBU

-

Rule #2: Be part of the european broadcasting area

-

Rule #3: Have the capacity to broadcast the entire event live

-

The combination of the first two rules opens up the competition to countries not conventionally considered “European”. The African and Asian coast of the Mediterranean are within the boundaries of European Broadcasting Areas and, as most of the countries in that region have television companies that are member of EBU (Algeria, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia), all of them are potential participants in Eurovision. Out of these eight countries, Israel is the only one that has regularly participated in the competition since 1973, winning the contest three times. Morocco was the only other country in the group to compete in 1980.

-

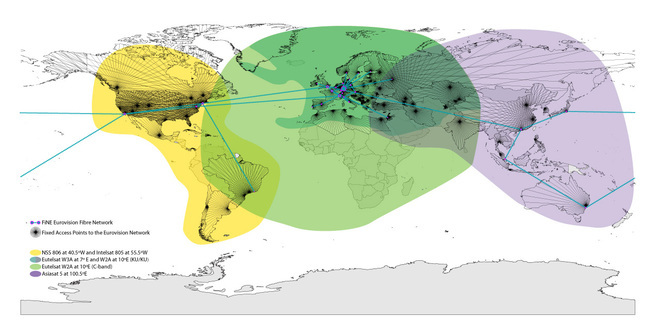

Map of Connectivity to Eurovision network in 2009

-

-

-

-

-

©2012 The authors and contributors

-