-

-

-

-

-

Projects/

Craig Rosman, Jonathon Meier, Dennis Tseng:

SuperLet

-

SuperLet creates an alternate market for affordable housing credits.

-

Introduction

Our world is becoming denser, and our infrastructure struggles to keep up with this trend. Meanwhile, city centers continue to lose their character and their affordability through the erection of soulless towers that house numerous ultra-expensive apartments and condominiums within shells of mediocrity. These apartments often have awkward floor plans drawn in an attempt to fit within the constraints of municipal affordable housing ordinances (like New York’s 80-20 rule). Looking around an American mega-city like New York or San Francisco, or even up-and-coming neighborhoods like West Oakland, Pittsburgh’s Bloomfield and East Liberty, or Durham’s American Tobacco District, one can see these towers sprouting up to accommodate the insatiable demand for urban housing.

To address this, we propose Superlet, a new type of commodities exchange that will have a significant effect on the way we envision our neighborhoods, our cities, and our skylines. We envision Superlet as a system to facilitate the efficient trading of affordable housing credits among developers and small landlords, helping to foster customizable buildings with character, while simultaneously giving landlords incentives to create and upgrade affordable housing units. All the while, economic diversity is maintained, and wealth is created for landlords, developers, and for the community. With Superlet we envision an invisible tool helping to shape the topography of cities and neighborhoods, allowing them to evolve organically, becoming more and more dynamic.

-

-

The Problem

As the demand for housing increases in urban centers nationwide, rents go up as a result of the dearth in available supply. Builders and renters start to move to previously under-served communities to take advantage of cheap land, and build new developments that largely charge market rates in addition to razing any historic character of the neighborhood. Meanwhile, floor plans, aesthetics, and functionality for developers are constrained by affordable housing quotas, ADA requirements, as well as significant public opposition to projects that are seen as taking away from previously affordable neighborhoods. Moreover, the small, distributed landlords that populate these neighborhoods are then pushed out by the developers who need entire city blocks to accommodate this complex footprint—these landlords are themselves unable to upgrade their aging housing stock, and, finding themselves unable to compete with the market-rate apartments for amenities and quality, they are pushed out of the neighborhood entirely. The resulting effect of these towers, which have a predilection towards gigantism, is what we refer to as the “Hong Kong-ification” of cities where mega-dense, unremarkable, and undifferentiated buildings go up right next to each other, and the desirable high-low cityscape disappears. The population within that neighborhood, or even within the city itself, becomes more economically homogenous, and the delightful things about living in a city—diversity, innovation through cross-cultural exchange, wonderful public plazas and spaces for communion—quickly disappear to make room for the insatiable demand for housing.

-

-

The Solution

With Superlet, we are developing a system in which landlords, large and small, can trade their affordable housing credits with developers, thereby creating monetary incentives for landlords to upgrade their stock, and for developers to customize their towers and create public amenities to complement them. This system will take the form of a ‘Housing Exchange,’ a kind of facilitated banking operation similar to a carbon bank, or any mercantile exchange. Superlet would function as the manager of these affordable housing credits (our unit of exchange would be “Units,” as in housing units, or units within a large development) and serve as the broker between all interested parties. As government sanctioned intermediaries, we would help facilitate the efficient allocation of Units and the creation of neighborhoods that accommodate residents of all income levels.

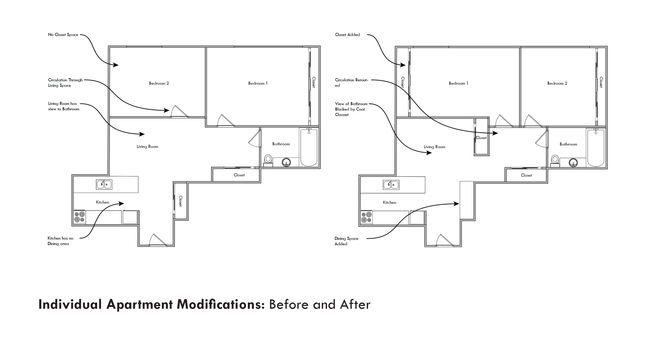

At its very core, Superlet is an urban planner’s bank, a financial tool with a broad mindset towards spatial consequences at both the micro- and macro-levels. It balances the concerns of the varying stakeholders and constituencies involved in shaping (and reshaping) cities and neighborhoods—residents old and new, developers and landlords, community organizations, preservationists, capitalists, government officials, and economic development wonks all gain concessions from the Superlet system. With Superlet at the helm of helping facilitate the efficient transfer of funds, we envision single-unit floor plans designed specifically for their potential users, buildings that are more aesthetically interesting and simultaneously more hospitable to residents, and entire neighborhoods gaining amenities and new residents.

-

-

How It Works

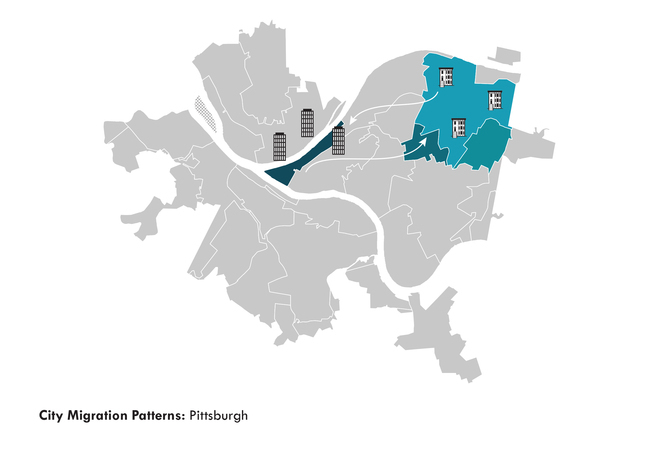

Superlet will incorporate as a for-profit entity whose primary mission is to function as a municipal economic steward. By functioning within existing borders of business improvement districts, economic empowerment zones, and municipality-defined neighborhoods, we can ensure that affordable housing is not moved to the fringes of the city, and that the positive effects of redistribution and reallocation are realized by the entire community.

Within these communities, Superlet will function as the exchange for Units (representing one housing unit mandated by the local housing development authority to be affordable), assisting in the purchase and sale of these Units between developers and small property owners. To remain economically sound, prices for these Units (in dollars) will be indexed to a 5-year difference between affordable rents and market rate rents in the local empowerment zone creating a huge incentive for landlords to sell their credits and use the money to improve their affordable housing stock, but not a prohibitive price tag for large-scale developers who can then use the freedom of needing less affordable units in their large buildings to construct towers that more closely reflect the character of the neighborhood, and are more efficiently designed to the needs of the incoming residents. Moreover, the municipality itself can contribute to the stock of available Units by contributing capital to create public amenities; as each of these communities develops, the surrounding commercial ecosystem and civic infrastructure must also be shepherded. This way, developers also have additional stock of Units to purchase in exchange for the promise of a public park or plaza, a grocery store, or partially financing a bus or rail stop.

To see how it might work in an actual neighborhood, imagine a dozen landlords in the Bloomfield neighborhood of Pittsburgh. These small brownstones have housed middle- and lower-income Pittsburghers for decades, and though the residents are happy with their neighborhood, their apartments have peeling paint, lack of access for people with disabilities, and have infrastructure that was built in the 60’s and is beginning to decay. Between all of the landlords, there are probably 50 units, with about 120 residents in total, but the landscape is beginning to change. Younger, more affluent folks are flowing into Pittsburgh to work in the thriving technology and biotechnology sectors and are looking for cheaper neighborhoods that are closer to the city center. Bloomfield is one of the primary targets for this group. As a result, other landlords in the area are posting their new units at markedly higher rates, and rents are going up across the board. Likewise, condominium tower developers are coming into Bloomfield with the goal of creating high-rise buildings to take advantage of the relative wealth of the new residents. In this version of the game, the small landlords have two options to keep pace with the growth of the neighborhood: drastically raise rents on their tenants, effectively forcing them out and renting non-upgraded housing stock to more affluent residents, or sell the entire building to a developer, effectively forcing their tenants out, and razing the original building to make way for new development.

Our story, the story of Superlet, is a happier one. In our world, the twelve landlords have another choice—they sell their market-rate rights to developers in the form of Units. This is an economically sound option for them—each unit is going for between $75K and $150K, depending on the differential between the affordable and market-rate rents. This means that a landlord for one of these brownstones can sell all of their Units for a total of $300K - $600K, providing a huge influx of cash with which they can upgrade their facilities and add amenities, all the while keeping the apartments at the affordable rate. It’s also quite a deal for the developers who can potentially buy the 50 units from all twelve landlords for $3.75 to $7.5 million, and thereby have the freedom to create a much more appealing and customizable building occupying a smaller footprint in the neighborhood, having already fulfilled any affordable housing requirements. So to recap, in our story, the neighborhood evolves in an organic and positive manner. Relatively affluent new Pittsburghers move to Bloomfield and find both delightful and functional high-rise buildings, as well as upgraded affordable apartments. Longtime residents of the neighborhood would be able to stay, and in fact get better facilities due to their landlords’ cash influx.

SuperLet is a project by Craig Rosman, Jonathon Meier, and Dennis Tseng.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

©2012 The authors and contributors

-