-

-

-

-

-

Infrastructure space/

Brian McGrath:

Zone Flood

-

Introduction

In February 2012, Prime Minister Yingluck Shinawatra’s decision to substantially increase the release of water from the major dams in the upper Chao Phraya River Basin marked a turning point in Thailand’s historical relationship of using water infrastructure as a medium of polity. If one accepts the traditional founding date of the first Kingdom of Siam at Sukhothai in 1238, the Prime Minister’s decision changed the course of 774 years of water infrastructure as a political art. Historically, the tributary paddy-state polities of mainland Southeast Asia maximized the annual monsoon’s rainwater retention to benefit wet rice cultivation. From the giant retention reservoirs of Angkor, to the upland village based systems of weirs and diversion canals of the northern Kingdom of Chiang Mai, to natural levee and vast canal systems of the Chao Phraya and Mekong deltas; monsoon rain water was diverted, retained and distributed over much of the alluvial plane in order to maximize agricultural productivity. Most accounts document the transition from local, pre-modern water strategies of the “quasi-hydraulic” tributary kingdoms of pre-modern Siam, to the development of western water management technologies by the Royal Irrigation Department at the beginning of the 20th century. In contrast, this paper will examine water infrastructure in the context of climate change accompanied by global water shortages and conflicts as well as disastrous floods, as beyond the control of the modern nation state.

What may have seemed as an act of decisive state craft on the part of Prime Minister Yingluck is in fact another example of what Keller Easterling has described quite literally as extrastatecraft. First, Yingluck was not a politician before the 2011 election, but a businesswoman and the younger sister of the notorious former Prime Minister of Thailand, Thaksin Shinawatra. While Thaksin remains in self-exile from the Kingdom rather than face sentencing following his conviction of corruptions while in office, he is an expert in remote technologies. A telecommunications tycoon before becoming a populist elected official, he advises his younger sister from his home in exile in Dubai. Traveling on a Montenegro passport, Thaksin recently celebrated the Thai New Year in April, 2012 by visiting the bordering cities of Luang Prabang, Laos and Siam Reap, Cambodia. He and his Thai redshirt followers were allowed free access to the monuments of Angkor in order to bask in the aura of one of the world’s greatest hydrological civilizations. One should also note that these two extra-state locations were former tributary states of the Kingdom of Siam before European colonial powers created national boundaries in the region.

As usual, during the rainy season of 2011, the Thai Royal Irrigation Department carefully stored water in the two great reservoirs behind the Bhumibol and Sirikit Dams on the Ping and Nan Rivers, both major tributaries to the Chao Phraya.The two dams, named for the King and Queen of Thailand, are monuments to a World Bank funded “technological transfer” from the Tennessee Valley Authority to post World War II Southeast Asia. In an era of global food shortage, the dams were a resounding success as Thailand became a regional “rice bowl.”Historical records show that water shortages were much more prevalent in the Chao Phraya Basin then floods, and the dams helped to secure the maximum productivity of the rice fields of the Central Plane. However, in much of Thailand, multiple scales of water infrastructure were often not a medium of paddy statecraft, but locally crafted at a village network level. Together these local systems and the state constructed irrigation infrastructure comprised a robust network that often produces three annual harvests and according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, has kept Thailand on top of the world's rice exporters since 1964.

In October, 2011, with the arrival of a late season typhoon from the South China Sea, northern Thailand was inundated with an additional deluge. This unexpected surplus forced the release of water at the over-capacity dams, engulfing the already saturated fields of the Central Plain of Thailand, and causing the worse flooding in over fifty years. Of course fifty years ago, Thailand was not a newly industrialized economy, and this recent flood inundated industrial zones as well as rice paddies. The flood became an international incident as seven of the industrial zones now ringing the agricultural terrain north and east of Bangkok were forced to stop production for months. A state policy of water retention for the maximization of export agricultural production ran into both the unpredictability of climate and the demands of maintaining the flows of the international supply chain of export industrial production.

Prime Minister Yingluck’s command to release 60 million cubic meters of water per day from the Bhumibol Dam in February, 2012 assured industrial investors of her resolve to prevent a reoccurrence of the financially disastrous floods of October 2011. This represents a major shift in water management as the economic strategy for Thailand has shifted from the retention and distribution of water for agricultural irrigation to one of keeping the expressways and industrial zones of the Central Plane dry for the production and distribution of cars and hard drives. The most recent data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture projects Thailand as trailing India and Vietnam in rice exports this year, as the Yingluck administration's populist rice price guarantee program has made the government the prime purchaser of rice, now in storage.

The question explored in these blog posts is what happens when the national policy of creating a zone of exception, in this case the high-tech industrial estates which ring Bangkok, flood. More and more common the logics of the zone are confronting the unpredictable forces of climate change. The spatial logics of contemporary industrial zones demand flat sites, proximity to good container port and trucking infrastructure, friendly government policy, and a cheap skilled workforce. The promotional material of Nava Nakorn, founded in 1971 as the first industrial promotion zone in Thailand, proclaims that it has easy access to all destinations in Thailand, including: four main ways to access the Bangkok CBD; a “labor haven” with 150,000 to 200,000 daytime population; and “international standard” infrastructure and utilities. However, in October of 2011, Nava Nakorn and six other industrial estates were under water, crippling the supply chain for hard drives across the world, and for automobiles throughout Southeast Asia.

When monsoon run-off swamped more than 1,000 factories across central Thailand, the world’s reliance on hard drives made in Thailand came as a surprise to many. As Thomas Fuller reported, “The image of Thailand as a land of temples, beaches and smiles has over the years been reinforced by the country’s tourism advertising campaigns. But the flooding here, the worst in at least five decades, has revealed to the world the scale of Thailand’s industrialization and the extent to which two global industries, computers and cars, rely on components made here.” Rising labor prices and the increasing value of the yen motivated Japan to create in Thailand “the Detroit of the East” in recent decades. Fuller also reports that the slowdown in car production from Japan to Pakistan as a result of the floods, is “a measure of Thailand’s importance to the global automotive supply chain” (NY Times, November 7, 2011).

The Thai Zone Flood is a tipping point in the water infrastructural history of the Kingdom of Thailand. Starting from the beginning of the 2011 rainy season, this blog will both trace the history that led to this particular confluence of the flows of water, politics and industrial supply chains, and also provide updates on the responses and reactions to the uncertainty of the tropical monsoon. Already the draining of Thailand’s reservoirs is causing concerns about droughts this year. The Thai Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Department counted a total of 20,628 villages in 277 districts of 36 provinces have been declared drought-hit since Feb 2, 2012, and as a result, dam discharge has been substantially decreased and fears of a water shortage for irrigation are brewing (Bangkok Post, April 2, 2012).

Zone Flood explores the transformation of water infrastructure in Thailand from a tributary political system of quasi-hydraulic paddy-states in dialogue with what James Scott describes as the artfully ungoverned mountain dwellers. At the end of the 19th century, the colonial empires of Britain and France demanded conditions on the development of the instruments of modern statecraft in the Kingdom of Thailand. Tributary Kingdoms characterized by relative autonomy down to the village level were organized into a polity of control centered in Bangkok. The modern history of the Kingdom has been fraught with tensions along the colonial borders, some which gave infrastructural jurisdiction over entire river basins (the Chao Phraya and its northern tributaries), while others subject to multinational control (the Salaween and the Mekong). The question around which these speculations circle is, in an era of climate change compounding water shortages and conflicts as well as flooding, how can water infrastructure become an extrastatecraft?

-

Storm Events

-

- Tracking Typhoon Nock-Ten

- Typhoon Nock-Ten

-

Typhoon Nock-Ten

On July 24, 2011, a powerful typhoon began to form east of the Philippine archipelago. In the subsequent few days Typhoon Nock-Ten proved to be one of the strongest of the season wrecking havoc across the Philippines, the South China Sea, Hainan Island, and VietnamI was in a small village near Udon Thani in the Northeast Region of Thailand when Nock-Ten passed. The Northeast, called Isaan in Thailand, is a broad dry Korat Plateau draining to the Mekong River to the north and east. Linguistically and culturally it had long been more connected to its neighbors in Laos to the north and Cambodia to the east than to the Chao Phraya Delta on the other side of the Khao Yai Mountains. To the west, Isaan is bounded by a series of mountain ranges and river valleys draining to Bangkok in the south.. In the mountains of Laos and Northern Thailand the Nock-Ten exhausted itself with a deluge of heavy rainfall flooding the Ping, Wang, Yom and Nan Rivers, and their smaller swollen tributaries. In the day following the storm, I traced this rolling landscape of flooded valleys following behind the track of the storm, witnessing first hand a havoc of uprooted trees, washed out bridges and roads. After many detours, I arrived in Chiang Mai.

The Northern cities of Chiang Mai, Lamphun, Lampang, Phrea, and Uttaradit were the first to flood. These are ancient cities, the seats of tributary kingdoms to the royal house of Ayutthaya from the 14th to the 18th century, and to Bangkok after 1784. Last year they were the locations of the first warning of what was emerging as Thailand’s worst flood in fifty years, as these upstream tributaries drained south to the already monsoon-inundated Chao Phraya River. In addition to the immense downpour from Nock-Ten, the major dams on the northern rivers had been storing water for off-season rice cultivation. The Central Plain of the Chao Phraya was water logged as well, as the monsoon season rice croup was maturing in the inundated paddies north of Bangkok megacity, protected behind its royal dike.

-

- Tracking Hurricane Irene

- Hurricane Irene

-

Hurricane Irene

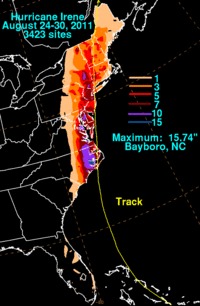

One month later, Hurricane Irene formed in the Caribbean and reached landfall at St. Croix on August 20 before proceeded on its slow march directly towards the sprawling Boston-Washington megalopolis. Hitting land at the Outer Banks of North Carolina, Southern New Jersey, Brooklyn and Connecticut, Irene felled trees and caused hundred year floods on the Potomac, Susquehanna, Delaware, Hudson, and Connecticut Rivers, as well as the numerous tributaries and smaller rivers in the urbanized northeast corridor. I had just returned to the U.S. as the after effects of Typhoon Nock-Ten were just beginning to play out in Bangkok, when a barrage of media warnings greeted me when as Hurricane Irene seemed to be headed straight at New York City. This time I found myself in Western New England, in the Connecticut River Valley town of Enfield, Connecticut when the tropical storm passed.

Like Nock-Ten’s effect in Northern Thailand, Irene mostly impacted the vast diffuse urban territory surrounding the large cities of U.S. northeast with its dependency on the asphalt surface of automobile infrastructure and the suspended power lines of energy distribution. As the flood events played out in Thailand, Bangkok was ultimately spared behind its dike and river walls, while the urban periphery, including its vast industrial estates, remained inundated. Similarly, Irene provided for the technocrats of the Bloomberg administration an opportunity to show off their emergency preparedness, as low areas in the city were evacuated and emergency shelters provided for the inundation that never happened. It was in this month from late July to late August 2011 that led to this project Zone Flood, with its emphasis on the infrastructural vulnerability of the peripheral urban territory, rather than our protected center cities. While the coming posts will focus on the Thai context from the perspective of the northern river valley city of Chiang Mai, I will return to Enfield as this years storm season plays out, continuing Benton MacKaye’s project of Liquid Planning.

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

©2012 The authors and contributors

-