-

-

-

Projects/

Jordan Carver:

Territory/

A Zone For Infrastructure Re-Purposing

-

Territory and context

-

The territory for infrastructure re-purposing examines how to pair state and economic policy adjustments with a large infrastructural project to create industry for the dismantling of Detroit’s abandoned structures and the creation of public transportation infrastructure. The territory in one sense becomes a zone, and like all other zones exists in a legal and spatial lacuna. It acknowledges the existence of and political acceptance of “public-private” partnerships, but is uncomfortable with it. Too often the public ends up subsidizing the private without the reciprocal benefits often touted by elected officials and business leaders. But can the zone become something different? Something less nefarious? Is it even possible to loosen regulations, create tax incentives and build enclaves within an urban environment and have any positive effects? At once slightly naïve and self critical, the proposed territory might respond to these questions with a solid, “maybe.”

-

Abandoned property in Detroit.

-

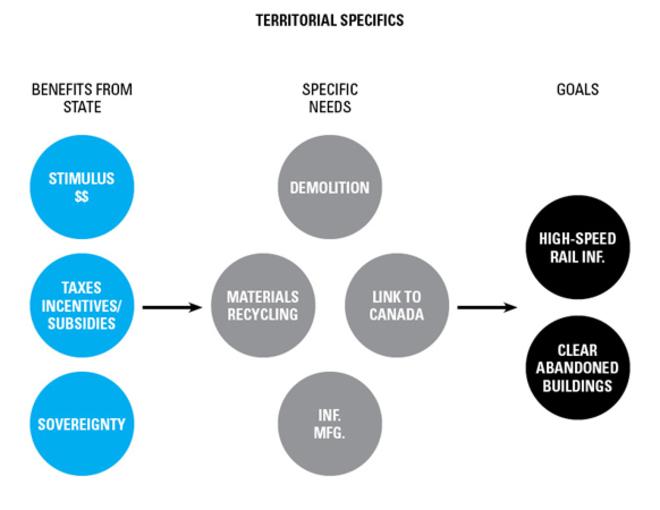

It is clear that Detroit has many challenges. Recent reports have shown that its population has dropped by 25% over the last 10 years, unemployment is at 11.1% and manufacturing, once its main economic engine, is gone. It’s not going to return. To deal with some of the abandoned land and structures Wayne County has been awarded over $57 million in Federal Stimulus money simply for demolition projects. On top of that, it has received over $60 million for small business development. This project looks at alternative ways to use this funding, as well as the potential to tap into the $45 billion left to spend.

In an effort to stimulate business investment Detroit has implemented the popular strategy of creating business and economic zones, in this case entitled “Renaissance Zones.” For Detroit these efforts have largely failed, one argument is they focus on relocating industry to Detroit—as opposed to dealing with the underlying economic and social conditions—and have operated largely for the benefit of private business interests. In addition, Detroit has placed limited time frames on the tax benefits, negating the cost of moving industry to the city without long term benefit. The site for this proposed territory occupies the old Packard Automotive plant, which sits entirely within one these zones.

-

Territory structure

-

The zone needs to be re-deployed, not as a driver for private business, but one that can be used for a public benefit. In the specific context of Detroit, there is a need to clear its abandoned structures, which number into the thousands, and can be re-purposed into base construction materials and infrastructure components to help instigate a high-speed rail network.

-

-

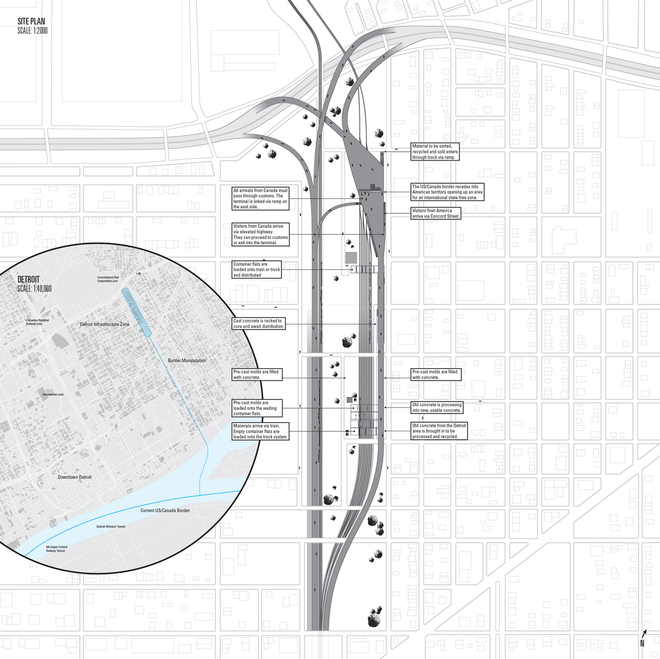

The repurposing of built material into rail infrastructure parallels the development plan detailed by America 2050 that calls for major rail infrastructure deployment in several “mega regions” throughout the country. To address some of the economics on how to build in Detroit, stimulus money would need to be granted. And to address the very real need to attract business, the opportunity to locate the industrial production within a nebulous zone of statehood and taxation arises from the specifics of the site and the international border.

-

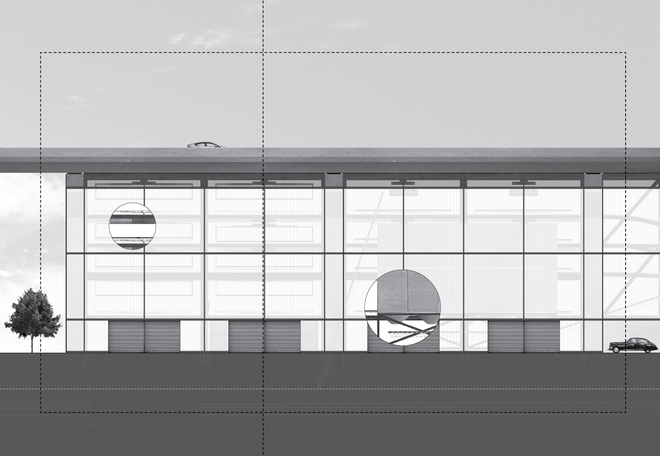

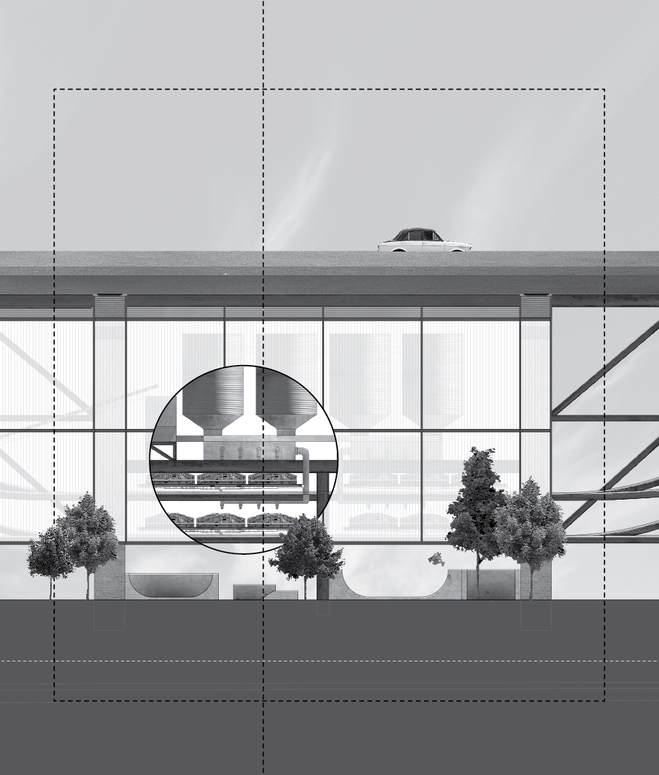

The elevated roadway contains an abandoned structure recycling plant, converting material into usable concrete.

-

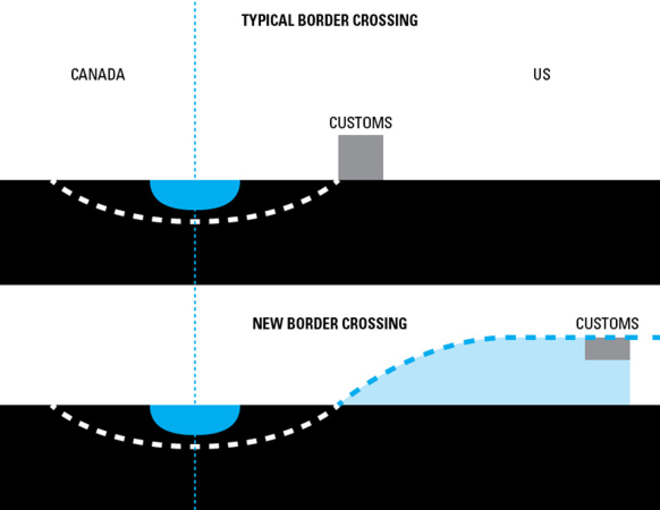

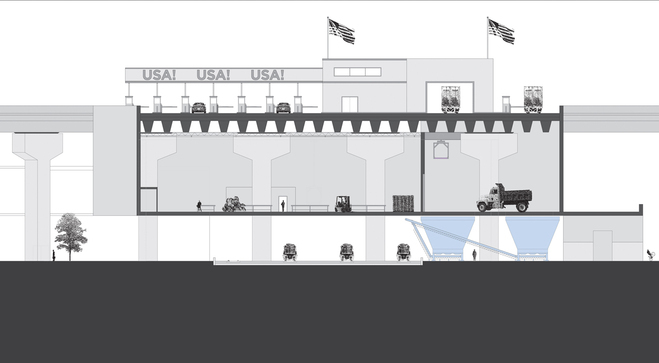

The zone is created by the addition of a new border crossing—a tunnel just south of the site. The need for a new tunnel taps into the plans created by the Detroit River Tunnel Partnership and sites it at the Packard Plant, due to its location within an already established transportation and distribution network and vast quantities of usable material. By pushing the official border crossing just north, to where it meets other transportation networks, the zone is established—at once on U.S. soil, yet still on the Canadian side of the border.

-

Material is cast into various rail infrastructure components

-

The very nature of moving the border crossing point North, which can be understood as a sovereignty reconfiguration, opens up a space for new economic policies to be implemented, operating in an established extra-state territory. And if the movement of a border point north can be seen as establishing the zone horizontally, or planar, raising if off the ground and maximizing the potential of an elevated highway can be a way to establish it vertically.

-

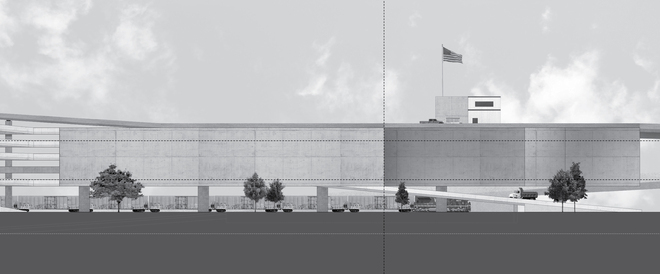

A new border crossing also houses material redistribution

-

The inhabitable border is a new sovereign arrangement

-

Restricting industrial management and production within the structure of the roadway allows it to be deployed over the site, supported from the ground plane, but independent of it, creating a self contained territory allowing for the implementation of policy adjustments, new taxation structures and governance independence.

-

Border crossing, infrastructure manufacturing, and distribution center

-

The problematics and potential in developing the territory, not to mention the political ramifications of border adjustment and a potential for lawless legislative results pushes the project into the realm of utopia—or dystopia. As conceived, the project is conceptualized from the specific needs of Detroit and the Nation, within the opportunities provided by the site and its context. When adjusting international laws, state sovereignty and economics to the benefit of business or the public good, the question of “what is the public good?” is always present. But when the majority of similar policies and sovereignty negotiations revolve around the exploitation of global capital, labor and resources, it allows for these tactics to be rethought and projected into new formulations with the hopes of a radically different outcome.

-

-

-

-

-

©2012 The authors and contributors

-