-

-

-

Infrastructure space/

JESSE LECAVALIER:

WALMART+VT

-

We never planned on actually going into the cities. What we did instead was build our stores in a ring around a city.

Sam Walton, founder of Walmart

-

Vermont was the last of the United States to have a Walmart store within its borders. Largely because of local conviction that the retailer’s presence in the state would increase traffic, threaten local businesses, and encourage diffuse suburban development, opponents waged a tenacious policy and media campaign that kept the company out of the state for several years. This struggle between the small state and the large corporation was seized upon by the news media whose coverage of the conflict consistently painted it in the colors of war by using headlines like: “Battle of Vermont: Walmart Plots its Assault on Last Unconquered State”; “Walmart Lost Battles, Won the War: Vermont Store Opens”; “Waging War on Walmart”; etc. (1) More than journalistic histrionics, the use of such imagery illuminates the military approaches adopted by both sides in pursuit of their aims. In spite of resilient opposition, Walmart continued its high-profile policy-based efforts to gain purchase in Vermont. At the same time, the company proceeded to systematically build a physical line of stores along the Vermont border. This blockade of retail outlets proved to be more potent than policy negotiations because it effectively saturated the market without ever entering it. By the time Walmart was allowed access to the state, the real battle had already been won.

-

Faced with Walmart’s imminent arrival, concerned citizens, flatlanders, “Ecotopians,” and even the Vermont government mobilized their resources to prevent the company’s entry into the state. (2) Most of the usual approaches were adopted including petitions, demonstrations, and the strict enforcement of design guidelines. However, in the case of Vermont, other more inventive measures were taken. For example, in an effort to raise awareness of the situation, The National Trust for Historic Preservation–a private non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation of historic places–included the entire state in its annual list of “11 Most Endangered Places” in both 1993 and 2004. (3) Though this inclusion has no immediate policy impact, it nonetheless holds significant sway over public opinion. At the governmental level, Howard Dean, former presidential primary candidate and the governor at the time, flew to Arkansas to meet with David Glass, the CEO of Walmart. According to Dean, "We had a good meeting. I don't think they'd had many governors come to meet with them. I wanted them to understand that we're not against Walmart, but that we're just against suburban sprawl… They agreed to consider downtown locations in the future." (4) As if seeking to broker peace with a hostile invader, Dean’s role as ambassador is significant because it implicitly elevates the status of Walmart beyond that of a mere retail operation. The governor’s focus on property and territory is also revealing. It asserts that the state has less opposition to Walmart as a retail enterprise, but instead takes issue with its choice of sites, which suggests that the conflict has less to do with ideology or aesthetics but more with simple location.

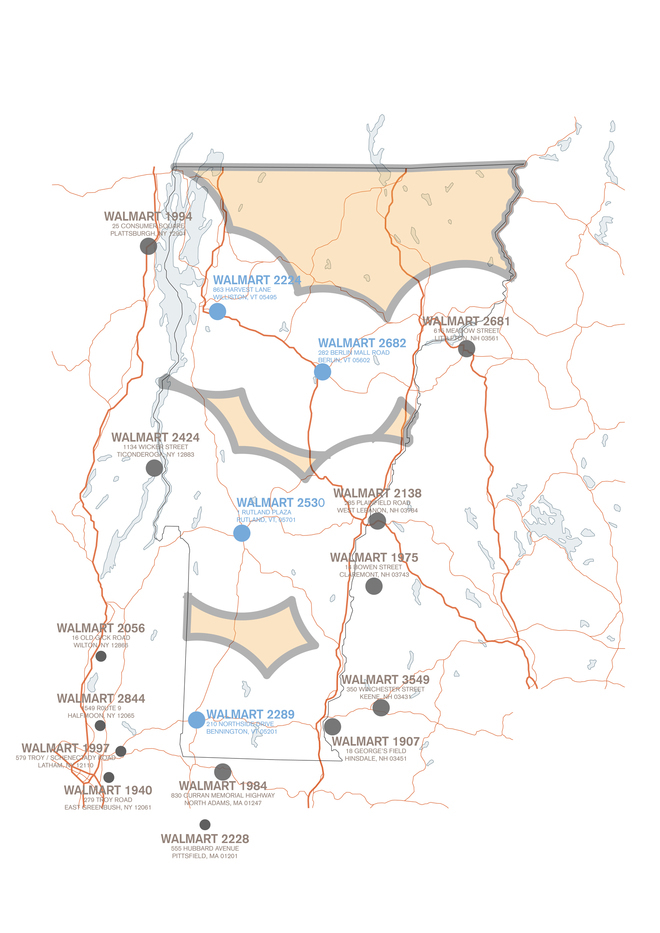

Spatial concerns have been a significant aspect of Walmart’s approach as it has consistently relied on a territorial strategy to expand its operations. As the company originated in rural areas serving a dispersed clientele, it adopted a procedure of peripheral market saturation. According to Walton, “We figured we had to build our stores so that our distribution centers, or warehouses, could take care of them, but also so those stores could be controlled…each store had to be within a day’s drive of a distribution center.” (5) A claim like this supports an understanding of Walmart’s operations as a dynamic totality rather than a collection of isolated retail locations and is significant because it helps illuminate how highly calculated their operation is. Walton goes on to write, “We never planned on actually going into the cities. What we did instead was build our stores in a ring around a city.” (6) This statement is supported by a 2006 study that found 49 percent of Walmart locations are within 500 meters of a city boundary, and 18 percent of stores are within 100 meters.(7) This same geographical precision of property acquisition played no small role in Walmart’s efforts to enter the Vermont market.

-

-

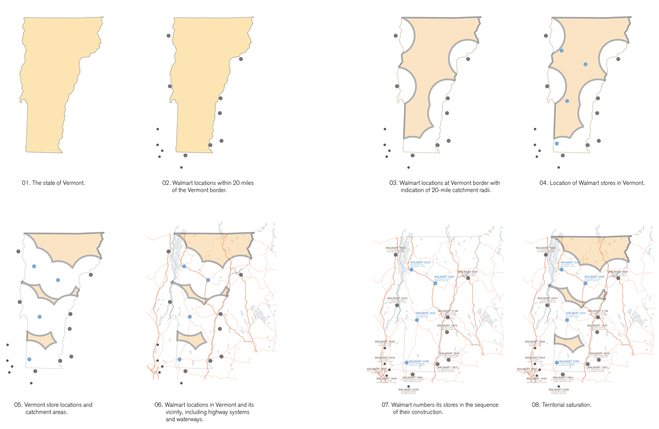

Walmart store locations in Vermont and within 20 miles of its border.

-

Walmart Supercenter 1907 in Hinsdale, NH. The river shown forms the border with Vermont.

-

Confronted, as they were, with intense opposition within Vermont, Walmart adopted an aggressive siege strategy and proceeded to systematically surround the state with outlets in an attempt to lure its inaccessible target market across the borders into New York, Massachusetts, or sales-tax-free New Hampshire. One reporter even suggested that Walmart was building a “Maginot Line of four open or soon-to-open stores along the state’s border.” (8) If Walmart could not enter Vermont, it would get as close as possible and distribute its locations to ensure saturated border coverage. There are seven Walmart locations within 5 miles from the border (two are even less than 2,000 feet away) and another six in a slightly larger ring around the state. (9) Taking a standard 20-mile radius as an index of coverage, the Vermont border is effectively sealed by Walmart stores. If one of the stakes in Vermont’s “battle” against Walmart is a kind of authentic “Vermont-ness,” then Walmart’s spatial tactics would, according to its opponents, threaten this quality. By encircling the state with precisely targeted retail locations, Walmart effectively acquired the market territory it was pursuing without entering Vermont itself. The state border that served as a political boundary is trumped by the “catchment areas” of the store locations and their strategic constellation effectively inscribes a new kind of elastic border within and around Vermont. Faced with the increasing migration of its tax-base, the state eventually agreed to allow Walmart entry into its domain.

-

Walmart store locations in Vermont and within 20 miles of its border.

Top, left to right: Albany, NY; Schnectady, NY; Saratoga Springs, NY; Ticonderoga, NY; Plattsburgh, NY

Middle, left to right: Williston, VT; Berlin, VT; Littleton, NH; Rutland, VT; Lebanon, NH

Bottom, left to right: Claremont, NH; Keene, NH; Hinsdale, NH; Bennington, VT; North Adams, MA

-

For further reading, see "All Those Numbers: Logistics, Territory, and Walmart" in PLACES.

-

NOTES

1. These articles include Frederic M. Biddle, “Battle of Vermont: Walmart Plots Its Assault on Last Unconquered State,” in Boston Globe, July 18, 1993; Malcolm Gladwell, “Walmart Encounters a Wall of Resistant in Vermont,” in The Washington Post, July 27, 1994; John Greenwald, “Up Against the Walmart,” in Time, August 22, 1994: Ross Sneyd, “Walmart Lost Battles, Won the War: Vermont Store Opens,” in St. Paul Pioneer Press, September 20, 1995; Pam Belluck, “Preservationists Call Vermont Endangered, by Walmart,” in The New York Times, May 25, 2004; George F. Will, “Waging War on Walmart, “ in Newsweek, July 05, 2004; and Alex Beam, “Walmart and the Battle of Vermont” in The Boston Globe, September 12, 2007.

2. “Flatlanders” is a term used by native Vermonters to describe outsiders who have moved to the state. “New Ecotopians” is a term established by the marketing firm Claritas to describe the demographic group made up of “consumers with above-average education who are technology-oriented and civically active. They are more likely than other Americans to make bread from scratch, drive a jeep, watch the Learning Channel and read Outdoor Life and American Health" (Gladwell, 1994).

3. The other entries for the 2004 list of “11 Most Endangered Places” include: 2 Columbus Circle, New York; Bethlehem Steel Plant, Pennsylvania; Elkmont Historic District, Tennessee; George Kraigher House, Texas; Gullah/Geechee Coast, South Carolina; Historic Cook County Hospital, Illinois; Madison-Lenox Hotel, Michigan; Nine Mile Canyon, Utah; and Ridgewood Ranch, Home of Seabiscuit, California; and Tobacco Barns of Southern Maryland, Maryland. The 1993 list also includes the following: Brandy Station Battlefield, Virginia; Downtown New Orleans, Louisiana; Eight Historic Dallas Neighborhoods, Texas; Prehistoric Serpent Mound, Ohio; Schooner C.A. Thayer, California; South Pasadena/El Sereno, California; Sweetgrass Hills, Montana; Thomas Edison's Invention Factory, New Jersey; Town of Ste. Genevieve, Missouri; and Virginia City, Montana. (Source: www.preservationnation.org/issues/11-most-endangered/)

4. Sally Johnson, “Vermonters are up against the Walmart - effort to stop retail chain from entering Vermont,” in Insight on the News, Jan 10, 1994.

5. Sam Walton and John Huey, Sam Walton, Made in America: My Story (New York: Bantam, 1991), 141.

6. Ibid, 141 (emphasis added).

7. Matthew Zook and Mark Graham, "Wal-Mart Nation: Mapping the Reach of a Retail Colossus," in Wal-Mart World: The World's Biggest Corporation in the Global Economy, ed. Stanley Burnn (London: Routledge, 2006) 20.

8. Frederic M. Biddle, “Battle of Vermont: Walmart Plots Its Assault on Last Unconquered State,” in Boston Globe, July 18, 1993. Perhaps it is worth noting that the comparison, however evocative, is misleading because the Maginot line of bunkers and fortifications was designed to serve protective and preventative purposes.

9. Though there are Walmarts in Canada, there are currently no locations within 20 miles of the Vermont border.

-

-

-

-

-

©2012 The authors and contributors

-