-

-

-

Infrastructure space/

Keller Easterling:

Zone

-

The zone has not always been the world’s global urban addiction. Once relegated to the backstage, it has, in the space of a few years, evolved from a fenced-off enclave for warehousing and manufacturing to a world city template. Yet the wild mutations of the form over the last thirty years only make it seem penetrable to further manipulation.

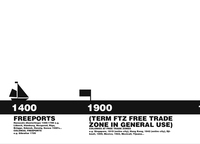

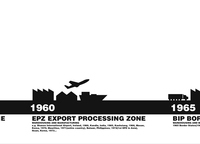

Free ports have handled global trade for centuries, but the mid-twentieth-century development of the Export Processing Zone, or EPZ, as a more formalized economic and administrative instrument, marks the beginning of the modern zone. With persuasive arguments about nation-building and free trade, the United Nations and the World Bank promoted the EPZ as a tool that developing countries should use to enter the global marketplace and attract foreign investment with incentives like tax holidays and cheap labor. Although intended as a temporary experiment and judged to be a suboptimal economic instrument, the zone spread widely during the 1970s even as it also spread new waves of labor exploitation. There were, however, unexpected consequences: rather than dissolving into the domestic economy, as was originally intended, the EPZ absorbed more and more of that economy into the enclave.

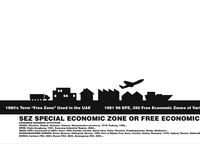

The next generations of the form, incubated in China or the Middle East, essentially became entire cities or city-states, rendering urbanism as a service industry. In the late 1970s, China’s experiment with the zone as a free market tool was so successful that it generated its own global trading networks, which in turn accelerated zone growth worldwide. For Dubai, the zone was a fresh form of entrepôt not unlike those that had figured in its longer history. As zones multiplied they also upgraded, breeding with other increasingly prevalent urban forms like the campus or office park. Merging industrial and knowledge economies, the zone has begun to incorporate a full complement of residential, resort, educational, commercial, and administrative programs—a warm pool to spatial products that easily migrate around the world thriving on incentivized urbanism.

Having swallowed the city whole, the zone is now the germ of a city-building epidemic that reproduces glittering mimics of Dubai, Singapore, and Hong Kong. While in the 1960s there were a handful of zones in the world, today there are thousands—some measured in hectares, some in square kilometers. No longer in the shadow of the global city as financial center (New York, London, Tokyo, São Paulo), the zone as corporate enclave is the most popular model for the contemporary global city, offering a “clean slate” and a “one-stop” entry into the economy of a foreign country. Now major cities and even national capitals, supposedly the center of law, have created their own zone doppelgängers, like Navi Mumbai, Astana, the newly minted capital of Kazakhstan, or New Songdo City, a Seoul double that developer Stanley Gale considers to be a repeatable “city in a box.” Economic analysts chase after scores of zone variants, even as they mutate on the ground, oscillating between visibility and invisibility, identity and anonymity.

As the zone mutates, it also resembles history’s various intentional communities with their mixtures of withdrawal and aspiration—mixing ecstatic expressions of urbanity with a complex and sometimes violent form of lawlessness. Maintaining autonomous control over a closed loop of compatible circumstances, the isomorphic zone rejects most of the circumstance and contradiction that is the hallmark of more familiar forms of urbanity. In its sweatshops and dormitories it often remains a clandestine site of labor abuse.

For all of its efforts to be apolitical, the zone is often a powerful political pawn. While extolled as an instrument of economic liberalism, it trades state bureaucracy for even more complex layers of extrastate governance, market manipulation, and regulation. For all its intentions to be a tool of economic rationalization, it is often a perfect crucible of irrationality and fantasy. And while as a spatial software, the zone is relatively dumb—the urban equivalent of MS DOS—it has quickly spread around the world. Yet, for all these reasons, the zone is ripe for manipulation, and its popularity makes it a potential multiplier or carrier of alternative technologies, urbanities, and politics.

-

-

Zone, Rotterdam Biennale, 2007

-

World City Trailers

An emergent genre of urban porn, urban music video or urban trailer now promotes the global city building epidemic. In the typical template for these videos, a zoom from outer space drops through clouds to reveal the location of a new world city. The stirring music of an epic adventure or western accompanies a swoop through shimmering cartoon skylines, resorts, suburbs and sun flares. A deep movie-trailer voice repeats all the mantras of free trade and incentivized urbanism to which foreign investment has become addicted—no taxes, no bureaucracy, streamlined customs, and deregulation of labor or environment law. This new free zone paradigm, often no longer the fenced in warehousing compound of just 30 or 40 years ago, nevertheless harbors grisly, stabilized forms of labor abuse, and it still fails to return optimal economic results. But egged on by global consultancies, the zone is now bathed in redemptive rhetoric and treated as the necessary signal for entry into a global marketplace. This selection of promotional videos, from among scores of others, demonstrates how contagious the free zone has been all around the world with examples from Tunisia, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, Georgia, Ecuador, Kenya, Taiwan, Afghanistan, UAE, Lithuania, Malaysia, India, Libya, Nigeria, Holland, Laos, Azerbaijan, Gabon, Tanzania and Kuwait. Comically drunk on heroic urban aspirations the videos distract from their inherent violence as they mix things like fantasy environments, Hegel quotes and buildings shaped like diamonds or dolphins.

-

-

-

-

-

-

©2012 The authors and contributors

-